by Eric T. Everett

The apple doesn’t fall far from the tree. And that’s a mighty good thing for jazz lovers and drummers alike.

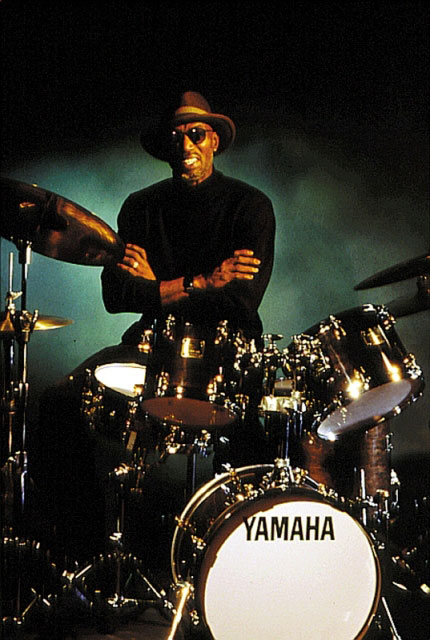

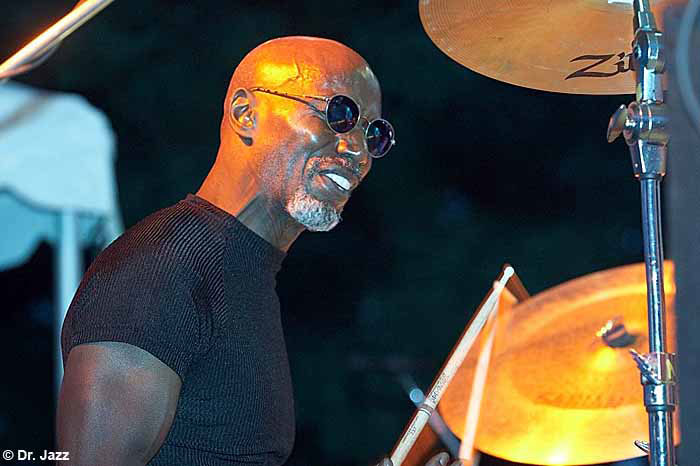

T.S. Monk, son of virtuoso jazz pianist Thelonious Monk, has carved out his own niche as a respectable and identifiable voice in bop drumming circles. But, he never forgot where he came from.

T.S. had the good fortune of soaking in all the musical vibes surrounding him at home. From receiving his first drumset from Max Roach to listening to his father, Miles Davis, John Coltrane or Art Blakey upstairs in his living room, there was no escaping it – he was presented with the ‘gift’ at an early age.

And since then, T.S. has spread the gospel of jazz across the globe, earning honors like New York Jazz Awards’ “Recording of the Year,” Downbeat’s “Reader’s Poll Award” for his critically acclaimed legacy to his father, “Monk on Monk.” He also heads up Thelonious Records and scouts promising musical talent as Chairman of the Thelonious Monk Institute of Jazz. Just ask world-renowned jazz saxophonist Joshua Redman.

But, beyond all this, T.S. can play! He swings hard with grace and respectfully tips his hat to Art Blakey’s Jazz Messengers, among others. T.S. is not shy – his enthusiasm for the drumming art and popular culture was delivered with passion, authority and rapid-fire recollections (not unlike one of his drum solos).

I had the opportunity to discuss his rich musical heritage, favorite drummers, dealing with personal challenges and what turned things around.

Many people have said that they hear Blakey and Tony Williams in your hard pop playing style. But, you began by playing funk and disco…

Monk: I absolutely love everything I have done. If the world loves it, well you’re lucky. I’m not one of those guys that runs from musical projects they were doing in the ‘80’s -- everything’s so serious now.

When I listen to some of the artists in jazz, it seems to me that those of us that have had that kind of diversity in our background tend to make, I think, better records at the end of the day. Because you know, it’s really the same influences.

I’d like to think that the paths I have taken or the path that Branford Marsalis has taken is similar to that of the Herbie Hancocks and the Wayne Shorters, in that we started out very, very straight ahead. Very serious and then you know, our ears opened up and we explored other things and then we came back to jazz with a lot of those other things.

For instance, when I listen to the sound of my drums, as much as I love Art and Max, it’s not an Art and Max sound on my kit. My sound is really a hybrid between that wide open sound of Art Blakey and Max Roach and a real, real tight sound that you might get out of the bass drum. That’s because I’m a baby boomer, and we had a pop culture experience of diversity that no longer exists.

You know, I was telling my daughter the other day, I remember when “Love and Marriage” was number one on the Hit Parade. “Twist and Shout” was there too, you know? And all of that used to come at you; so I think those sensibilities that you get from the variety have an effect, particularly on drummers because of the rhythmic influences. The impact of John Coltrane or David Sanborn -- it’s there!

Who were your drumming influences?

Monk: The thing I learned from Max Roach, Buddy Rich, Gene Krupa, Cozy Cole, Sid Catlett, Chick Webb, Ed Shaughnessy, Chico Hamilton and all the great drummer band leaders is when you listen to their records, they don’t fill their records up with a lot of drums. They get the baddest musicians on the planet that they can find and they play stuff that is really tight and really together. They know how you have to be a supporter -- you’re the drummer, you’re not the trumpet player. So you get underneath everybody.

Take this example. Often people go to a dance and the band has a drummer that can really play a lot of stuff, right? If you ask people after the dance, they will say, the drummer was loud. Now you take a drummer that gets in the pocket, gets under everybody and keeps everything thumping, right? You ask people, ‘How was the drummer?’ They say, ‘The drummer was great!’

How does one go about achieving his or her sound?

Monk: I don’t hear very much attention paid by artists to the tuning of their drums. Because Tony Williams tuned his drums differently from Roy Haynes who tuned his drums differently from Buddy Rich who tuned his drums different from Gene Krupa.

Find your own sound. The wonderful thing about our instrument, and I tell young drummers this all the time, is that we have the newest, the most recent of all the modern ensemble instruments -- the trap drum kit.

We don’t have a standard size stick. If you play the violin, everybody’s playing with that standard bow. There’s no standardized drum size, configuration or cymbal size. We have no standards so we’re really free, more free than any other instrument to create an identifiable sound that is associated with us as individuals.

And I don’t see drummers taking advantage of that anymore. The last really modern drummer in jazz with a specific sound that you say, ‘Oh, I know who that is,’ is Jack DeJohnette. He’s the last guy on the drums in the last part of this century to really identify himself.

You resort to the older method of controlling sound by dampening your bass drums and toms with duct tape. Can you elaborate?

Monk: Generally when I’m on the road, I’m the king of duct tape because duct tape allows you to change the weight of the head. And so as a consequence, by changing the weight of the head, you’re going to change the way the head responds to the stick. I found that duct tape allows you to be fairly specific in the weight because different size pieces address the muffling in different ways. But, if I don’t have a duct tape I will use a wallet, or I will take my jacket off and drape it over the front of the bass drum to the chagrin of Yamaha.

What advice do you have for younger, jazz musicians today?

Monk: I think that a lot of jazz musicians, younger jazz musicians, tend to take license from Monk and Coltrane and all these other great artisans and think that they can just play whatever they want to play any way they want to play it, not understanding that those guys paid their dues. Those guys played it the way it was supposed to be, the way it was written initially and then they editorialized.

If you listen to all the early records by any of the great piano players that you love, including Herbie Hancock and other modern guys, you’ll find their early records were full of standards. They’re great composers but they first paid their dues -- they learned how it was supposed to be done. They learned what had proceeded them and how you play it right and then, and only then, they say, ‘Okay, now I want to play most tunes THIS way.’ So, by the time Herbie Hancock rearranged “Round Midnight,” he was qualified.

While you grew up in a musical dynasty, you were challenged with personal adversity that took you away from drumming for several years.

Monk: The last two years for me have been very, very tough because I had contracted Hepatitis C some 20 or 30 years ago. And I was fortunate enough that my doctor was involved in a trial of a new treatment for the disease. That knocked me off the scene from really around October 2007 until January of 2010. I didn’t take any gigs -- I just disappeared off the scene.

I’ve had it harder in the last two years than I did in the previous decade. It’s not since I was a teenager that I’ve had six or seven hours a day to just practice and work on things. When we started the Monk Institute, we were doing all these things, including a performance at former President Bill Clinton’s televised inauguration.

Then, previous to all of that, I had a tragedy with my sister and the whole RB thing, that’s why that came to a screeching halt. I lost my sister and the other lady, Yvonne Fletcher, both to breast cancer, within four months of each other in 1983. It completely devastated my life and so I stopped playing from 1985 until 1990. I didn’t touch the drums, and I only got back on the drums as a result of starting the Thelonious Monk Institute.

And then the most extraordinary thing happened to me -- In 1991, the Institute did its first outreach program. We did it in the state of North Carolina. We did twelve schools in ten days with a group teaching the history of jazz. Max Roach was the first artist we ever took out with us.

We had set it up so that we’d take along Max’s drum kit but also have a demonstration band so that if Max wanted to talk about the blues, he didn’t have to go run over to his drums and play the tune. He’d say, ‘Hit it, fellas,’ and the guys could play the blues. Well, two days before the event, the drummer couldn’t make it, and I’m told that I’m going to have to go play the drums for this thing. So I’m moaning and groaning but I say, ‘Okay, it’s a demonstration band, everything is cool. I’ll do it, I’ll do it for the cause, right?’

You’ve had quite a personal musical journey, haven’t you?

Monk: I’ve been through many stages of my career, you know, like the ‘Monk on Monk’ thing in ’98 was like when I first came out as a jazz artist, everybody wanted me to make this album. ‘Well, you just need to get an all-star band together and do all your father’s music, blah, blah, blah and it will be great and you’ll sell a million records.’ And I said, ‘Yeah, and then nobody will ever hear from me again because they’ll all say, oh he’s got Ron Carter and everybody on his record, who the hell is he?’

When you start talking about me doing my father’s music, it sounds real easy to you because his name is Thelonious Monk and so is mine. But, I’ve got to do this right. If I do so, I’ll make a great record and everybody will love it. If I do this wrong, people will resent it.

And so that’s why it took me until 1998 to do ‘Monk on Monk.’ But that album did a lot for me and my career. Before ‘Monk on Monk,’ my interviews were basically 25-30% me, 75% my father. After ‘Monk on Monk,’ it flipped, and my interviews became 75% me, 25% my father.

Before that, I shot out of the cannon with ‘Take One,’ with a whole bunch of guys that could really play their asses off, real solid veteran players with no superstars and a bunch of music that nobody was playing to sort of establish that I could actually play.

‘Cross Talk’ is full of wonderful things. I sing a version of ‘Somebody Found Me a Dream’ by Oscar Brown Jr.

I’ve been on the major labels, I’ve been on the minor labels, I’ve had the R & B hits, I’ve had the jazz hits. I’ve done all that stuff and at this point in my life, I’ve got to start reaching for where I want to go as an artist. I’ve done the Thelonious Monk Jr. dance so everybody knows that I’m locked into daddy but now I’ve got to be me and this is where the courage really comes in and so I made a record which is a really nice called ‘Higher Ground.’

Right after I made ‘Higher Ground’ was the beginning of me getting sick and I didn’t know it. You know, so it’s been almost four years since I did another record.

What do you have on tap? What’s next?

Monk: Next for me is my album which will be my first album in 3-1/2 years. The record that I’m going to work on now I feel is like almost a reintroduction for me because I haven’t had a record in so long, although I’ve been working the whole time and the crowds still come. I pack the house and get great reviews.

The new record will have a lot of different stuff on it because that’s really who I am. So I that’s why I didn’t want to go back and get another record deal with a label because I don’t want any controls on me at all -- I’m going to do some singing which I like to do, and it’s going to have some stuff that really deals with rhythm. I also want to do some stuff with some African drummers.

I’m just going to have a ball making a record of the music that I love which means probably having something really straight ahead to reestablish that oh yeah, he can play that real serious, serious drop dead straight ahead stuff. It’s going to have stuff that’s funky and probably something that’s childish and it’s just going to be a cornucopia of who I am because that’s me as an artist.

So, can you offer some final words of wisdom from someone who had the unique perspective of sitting on the lap of one of America’s most innovative forces in 20th century music?

Monk: The thing that I learned from my father and from all of his peers was that at the end of the day in jazz, if you don’t just dig who you are, you’re never really going to be happy and a lot of people are not willing to be who they are because they’re afraid that they may not be accepted. Well you know what? I watched my father, I watched a whole bunch of guys, and I’m going to be who I am and you’re either going to dig me or you won’t. I ain’t going to play you nobody else’s stuff -- I’m going to play you my stuff.

---

Eric Everett is a freelance writer and drummer for the Eric Everett Jazz Ensemble.