Feature Article by Keith Fisher

There have been some musical instruments produced over the years that could lay claim to being “a work of art”, but I suspect the eye of the beholder invariably belonged to the musician – the beauty largely unrecognized by the general public… not so this Gretsch Centennial. Never had I heard comments from women in the audience about 'that beautiful drum-kit' or praise from guitarists and pianists about how incredible it sounded until I took the ridiculous decision to gig this rarest of rare and finest of fine gold and Elm-Burr masterpiece in the pubs and clubs of my home town. For the first fifteen years it never left my house – except to make its perilous journey from Los Angeles to England – and sat in glorious silence, hidden from the world, untouched by stick in anger. Now, because real glory belongs to the people who crafted this instrument to such a monumental standard and to the man who conceived of such a fitting testament to a company that led the world of drums for so many decades, I decided that by far the greatest tribute I could pay to those people was to play the kit. I am further obliged however, to explain how such a rare and valuable instrument came to exist, and furthermore, came into my possession. So, let me start at the beginning and explain briefly why these drums were made and why there is so much mystery concerning them.

In 1967 Fred Gretsch Junior was sixty years old and without an heir. The company his grandfather had started – family run for eighty-four successful years – was about to be sold! The ‘Sixties music scene was happening and the Baldwin Piano Company was knocking at his door: they needed drums and guitars to expand their market. Twelve years later they bought Kustom Amplifiers and with that company came Mr. Charlie Roy, who set about reviving a drum company that had not even produced a new catalogue in seven years. So profound was his involvement in revitalizing the company that in 1982, Baldwin, who were obviously totally out of their depth, offered to sell it to him. The story up to this point is well documented history, now we enter the twilight zone.

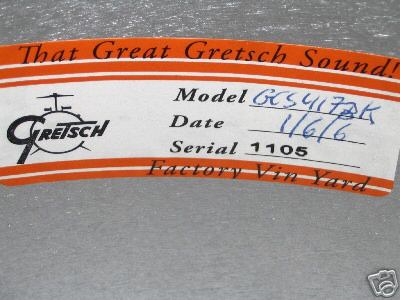

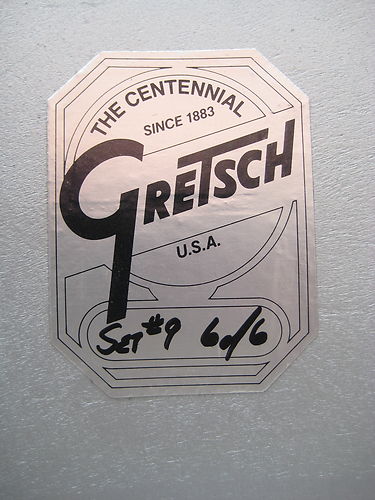

In 1983, on their stand at the Frankfurt Trade Fair, in stark contrast to the majority of drum manufacturers – who in Tama’s case had three floors of displays – Gretsch had one drum kit! A jazz kit, finished in Bird’s Eye Maple with gold plated fittings. A numbered, limited edition with a special new badge and every drum personally signed by Charlie Roy as part of a series of one hundred kits to celebrate the hundredth birthday of the company. According to the Gretsch staff, this was not a production run: every kit would be ‘made to order’ to the specifications of the customer. No brochure was produced, all that was shown to the dealers of the world were photographs of the three wood veneers available and after that it was up to the customer to say what sizes were required. The other two woods were Burl Walnut and Elm Burr. The drums were fitted with specially commissioned heads from Evans in a mirror gold finish. Even the snare wires and the drum key were gold plated. Any of the three finishes were available with chrome-plated hardware if desired. Each of the drums was given a special silver badge inside the shell that identified it with the set: in the case of my seven-piece kit (set #19) the bass drum was 1 of 7, while the snare drum was 7 of 7. The new outer badge featured the set number and also Charlie Roy’s signature in gold on bronze. Alongside all of this a customized satin tour-jacket was included, and it featured your name under the Gretsch logo on the front, and on the back was “THE CENTENNIAL” and an embroidered depiction of the kit. This meant you could flaunt ownership while the kit stayed safely in the house. Truly a collectors dream!

Needless to say, the quality of the finish of these drums was nothing short of exemplary. The use of Elm Burr veneer for instance, sourced in the Carpathian Mountains, made the cost fantastically high compared to a standard maple finish, so the lacquering and polishing were accordingly exceptional. The pride and attention that the staff normally took with Gretsch kits was always of the highest standard, but they still managed to ‘go the extra mile’ with this birthday series. The move to DeQueen, Arkansas had put the Gretsch factory in the heart of the American furniture belt, and consequently, the standard of wood finishing was superb. These were people who understood the treatment and development of wood and took enormous pride in the quality of production. To apply quarter-sawn veneers to the drum shell cylinders was an astounding achievement! An article in Modern Drummer magazine back in 1983, detailing a visit to the factory, left us in no doubt just how much care was taken over the finish and that these were exactly the right people to achieve such a result.

John Sheridan, in his article on the series for Classic Drummer, remarks upon the curious difference in the sound of the drums produced at the DeQueen plant and the subsequent demand amongst cognoscenti for shells from that period. I recently set about establishing the exact shell construction after a question was asked on the Gretsch Woodshed forum and discovered that my shells are actually thinner than normal Jaspers supplied to Gretsch in DeQueen at that time – even including the outer veneer – at 5 instead of 6mm, and effectively only five-ply rather than six. The ply material and grain orientation followed the standard Jasper format for DeQueen Gretsch; however, this generated a separate article to explain fully. The top and bottom of it all was that the Centennial construction was actually different again to the current production models and is one very thin, unreinforced shell.

If you think that all of this was a lot to offer the drummers of the world, and demand would obviously far outstrip availability, bear this in mind: back in 1985 the cost of a seven piece power-tom rock kit with an 8” snare and a 24” kick but without any hardware other than the tom-tom holders and their posts was $7,800. This was definitely an “exclusive” edition! Unfortunately, for reasons best left in the boardroom, Mr. Roy was forced to relinquish the presidency of the company which was returned briefly to Baldwin and the task of signing the badges was assigned to marketing manager Karl Dustman, before the company was once again returned to the Gretsch family’s hands.

My kit had been ordered by the owner of an instrument shop in the San Fernando Valley. He had intended to play the kit himself, but after waiting over two years for its delivery he adopted a DW instead. So when, in 1985, the kit finally arrived, he put it in the window and offered it for sale. As he was piling it up I arrived, saw the kit, walked into the shop and bought it there and then. As I said, the recommended retail price was $7.800.oo but I got a good deal because he had not even been invoiced for the drums and I was standing there with cash in my hand. I saw four other Centennials on sale in shops around LA during ‘85 and ‘86 – two featuring the alternate finishes – but I also sensed a certain blasé indifference to their presence: perhaps because of the price, and perhaps because this was the era of electronic drums, and wood was seen by many as ‘Jurassic’.

One hundred is actually quite a high number, considering what an exclusive project this was; plus, Gretsch was actually sitting in limbo all during this period – effectively without an owner – while the family got all their ducks in a row and were able to buy back the company at last. I don’t think the world had any idea how close we came to losing Gretsch forever; without the concerted efforts of the family that is precisely what would have happened. In the midst of all this broo-ha-ha it is not surprising that the records of sales and ownership were lost. I never got my jacket – that is for sure.

For fifteen years I kept the kit at home, playing my ’72 Rogers Butcher’s-Block Londoner instead; then on the eve of 2000 – to celebrate the millennium – I decided to bring the kit out and gig it. I have gigged it ever since, and not an event has gone by where someone didn’t come to me and praise the beauties. I’ve actually had women come up to me and ask if they can stroke it! Many drummers find it difficult to accept that I am actually gigging the kit: wearing all the gold off the snare drum rim and generally reducing the kit to decidedly second-hand. My response is that it’s mine and it’s paid-for and it’s going to get played; besides, if you look and listen, then it really demands to be seen and heard. Gold can be re-plated, varnish can be restored; other than serious damage it’s all redeemable.

Since I first began the research and initial drafts of this article back in ‘93 – for a Japanese drum magazine – I have uncovered precious little in the way of fresh information. Despite having asked Charlie Roy – via his son – I’m still confused and mystified regarding the number of Centennials that were actually finished and sold. Karl Dustman is uncertain. Even Duke Kramer couldn’t recall. Nobody seemed to know. Apart from watching Ebay religiously, I had a website up and running for a few years that linked to various suitable locations in the hope of finding all the owners of the 100 kits – if in fact they existed. I found seventeen counting the maple kit at the trade fair! Then Stan at Pro Drums told me of a jazz kit that went down to Orange County for a baseball player. Phil Collins told me he had one. I’m pretty sure Charlie Watts has one. Also, Jeff Poccaro had a set – which is now with Joe – that was used extensively on his recording sessions. Recently, this article posted on the Gretsch Woodshed site has unearthed a further two kits: one elm, one maple. Most folk have never seen anything other than Elm, but I saw both alternative offerings in the 1980s, and I know of three Bird's Eye Maple kits around today (two in Texas). Charlie Roy told me that he has the only kit made with the brass fittings (#11) that were originally intended. I have photos of kit numbers: 9, 19, 22, 25, 33, 47, 50, 53, 67, 70, 79, 89 and 93; all with Charlie Roy's signature on the badges.

Where are the remaining 70-plus kits… assuming they all exist?

There was a lot of gold-plated hardware left in the Gretsch warehouse afterwards, and at one point in the mid-nineties it was offered for sale to the general public: the intention being that you could replace your chrome fittings and customize your drums. The other remains of the project – un-drilled shells in various finishes – have also gradually appeared as occasional special-edition offerings over the years. The badge on one 14 x 8 Elm snare drum was a Centennial, but instead of a signature it was marked ‘Vineyard 83’, after a comment made by Vinnie Colaiuta (he called the warehouse a “drum-vine”) during a visit to the Gretsch premises back in the late ‘nineties. A 13” soprano snare drum in walnut veneer was on the market in 2006 and it was obviously taken from an undrilled tom-tom shell as there were no such snare-drum sizes around in the early eighties.

Given that I am now based in England, and also considering that the Gretsch company was seemingly hidden behind an iron curtain – passable only by the chosen few – for the late 'eighties and all the 'nineties, plus the air of mystery that already surrounded the series, I can only tell you what little I have learned from watching the market with regard to quantities, locations, and styles of the other kits. Even Mr. Gretsch has no additional information that might shed some light on the series; perhaps one day I will finally put an end to the mystery surrounding this magnificent tribute to a drum company that has remained at the forefront of its world for 130 years. There again, maybe it does no harm to the prestige and reputation of Gretsch to have a little mystique attached here and there.