by Ryan Patrick Henry

The forgotten story of how one Aviation Machinist’s experiences during WWII would lead to an innovation in modern drumming.

(see larger pictures and captions below the article)

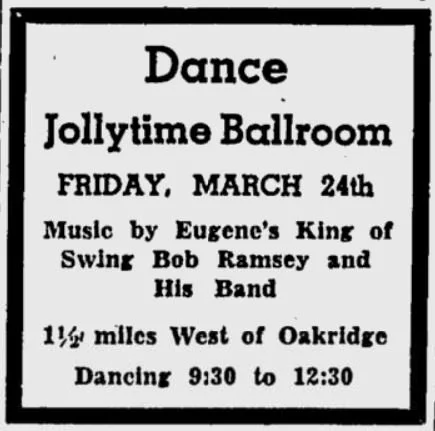

It was the winter of 1940 and Bob Ramsey couldn’t have been happier. He had spent the past several years honing his chops as a jazz drummer in the local clubs and dance halls around Eugene, Oregon, at first backing other musicians and then as his own bandleader. Bob Ramsey and His Band started out as a 7-piece dance orchestra and quickly swelled in ranks to a full 10-piece big band. They became so popular around Oregon’s college campuses that word was out in the papers- Bob Ramsey was a real “hot” drummer! Things were going great with his sweetheart, Margie, and they looked forward to all the dance concerts and good times the new year would bring. But, the Axis powers had other plans; a year later the world would be at war and “Eugene’s King of Swing” would find himself floating in the middle of the Pacific.

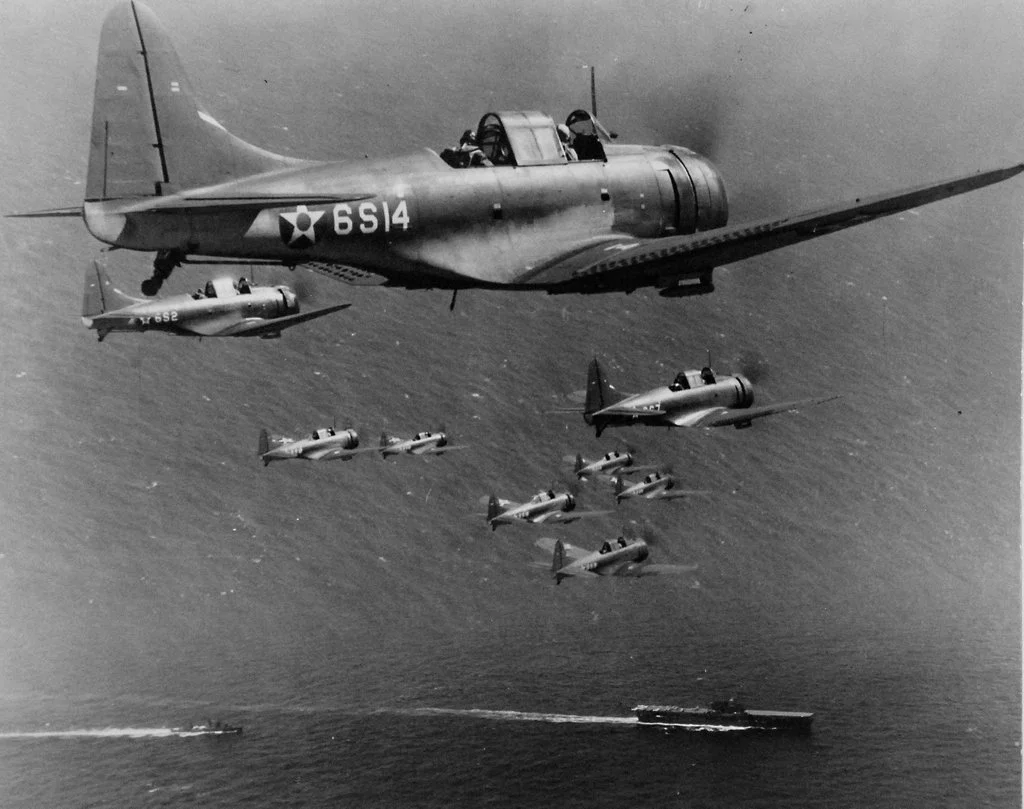

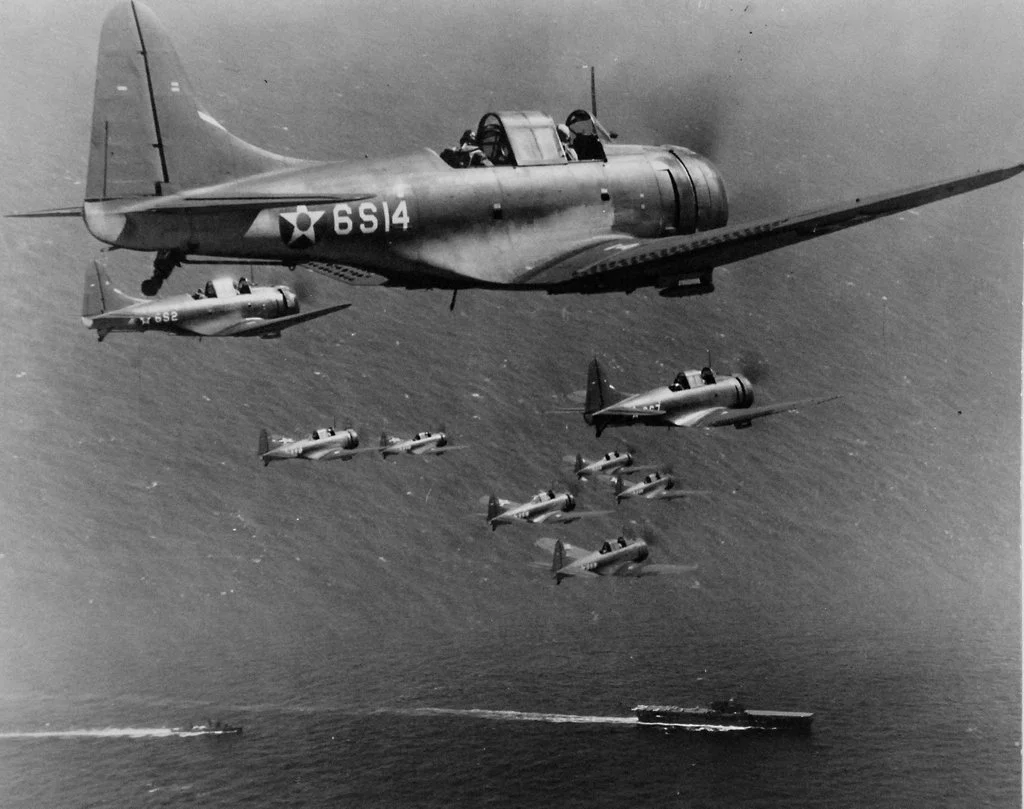

Bob and his friend Harry Spence, a fellow musician from Eugene, volunteered for the U.S. Navy together. Bob wrote home for a column in the local newspaper about their experiences, joking in the Eugene Register-Guard that his new M1 rifle was “slightly heavier than a pair of drumsticks.” Before long they had earned their stripes, and Bob was now an Aviation Machinist’s Mate 2nd Class aboard the USS Enterprise (CV-6) aircraft carrier serving Scouting Squadron Six and their complement of Douglas SBD Dauntless scout bombers. Working with the Enterprise Air Group he also saw or serviced Dauntless SBD dive bombers, Douglas TBD Devastator torpedo bombers, and Grumman F4F Wildcat fighters. It was hard to believe that just a year earlier he was “dropping bombs” on the bass drum and crashing cymbals in frenzied drum battles on the bandstand. Now his battles were on a carrier under the crash of artillery shells as he helped to drop real bombs on the enemy.

During his tenure on the Enterprise, Bob participated in 12 major engagements in the Pacific, nearly every one in the first year of the war including the Marshall, Wake, and Marcus Islands. His Enterprise Air Group provided air cover for Task Force 16 accompanying the USS Hornet (CV-8) and her B-25 bombers to launch the legendary Doolittle Raid, the daring retaliation for Pearl Harbor that, for the first time in history, struck at the heart of the Imperial Japanese mainland. They then went on to fight the Battle of Midway and Guadalcanal, among others. Despite often incurring heavy damage including multiple kamikaze attacks, each time the Enterprise would somehow emerge largely unscathed to the dismay and disbelief of Japanese officers. Battle damage to the Enterprise was so severe that the Japanese incorrectly reported her as sunk on three separate occasions. Such an impressive record of uncanny resilience earned her the nickname “The Ghost,” as if the Enterprise was a phantom that had somehow returned from the dead to exact her vengeance.

According to Bob, “As most people know, our fleet was heavily damaged at Pearl Harbor, Dec. 7, 1941. This left the Enterprise to go after the enemy in such a fashion that they didn't know who it was or where it came from, so it became a foe from the fog or foul weather or night. This reaction prompted the famous correspondent, Walter Winchell to give the ship the tag, The Gallopin' Ghost of The Oahu Coast. 1942 proved to have its work cut out for the Enterprise and she stepped into the assignment with gusto, hitting the enemy from here and from there- sometimes light, sometimes hard, sometimes hurt, but still slugging it out. It was no more than right that this gallant ship should go through this terrific struggle to become known as the greatest ship of our history.”

By the war’s end Enterprise aircraft and artillery had downed 911 enemy planes, sunk 71 ships, and destroyed or damaged another 192. The daring exploits of The Gallopin’ Ghost of the Oahu Coast would earn her a Presidential Unit Citation (the first awarded to any ship), the Navy Unit Commendation, and 20 Battle Stars, making her the most highly decorated ship of WWII. For his service, Bob was awarded two Silver Stars and two Bronze Stars. However, it was not the action during any of these battles that would come to shape Bob’s postwar years and the course of modern drumming, but a chance encounter between battles at the machinist’s bench.

One day during a lull in the fighting, the ship’s drummer approached him with a problem. He had broken the pedal for his bass drum and hoped Bob would repair it. Bob was more than sympathetic, having had his own similar experiences with the drum pedals of the day. As someone who had spent hours at a drum set tirelessly working a kick pedal to keep the crowds dancing, he knew that a broken pedal was a show stopper. During the war it was no different, as music was integral to high morale. Amongst the musicians and machinists, the spirit of innovation was in the air with each ready to go the extra mile to get the job done. This broken drum pedal was just another weapon in the fight against the Axis powers, and as a military machinist he would give it the same fastidious, meticulous care as any of the aircraft engine parts that came through his hands. He began to consider the repair and thought back to his own problems with similar pedals. Suddenly, he decided he was not going to fix the pedal after all. He would do his crewman one better- he would make him a new, better designed kick pedal.

Bob recalled the slew of pedals he’d tried over the years. “I had the feeling there should be a better mechanical arrangement for a drum pedal, since the only ones on the market gave me leg cramps after a long session,” he told Susan Shepard of the Springfield News. Like the rise of aviation technology over the past century, the drum kits of the day were still transitioning from their formative stages into what we now know as a modern drum set.

He envisioned a sturdier drum pedal with a faster action that would kick with the speed and rapid-fire precision of the .50 caliber machine guns on the airplanes he serviced. By contrast, most of the pedals available on the market seemed woefully underbuilt with a single, underpowered spring. They would often squeak loudly and were difficult or impossible to adjust, with slow and cumbersome action. Many of them were made with leather straps connecting the foot pedal to the beater arm which could break as the leather wore out. Some players he knew complained about the beater arm coming back too quickly and striking them in the shin, while others lamented that the beater would not retract in time to strike the next note. Bob would address all of these issues in his new design, which drew some inspiration from his aviation experiences aboard the Enterprise.

William F. Ludwig Jr., former president of Ludwig Drums recalled the pedal’s design, “The ship’s drummer broke his pedal and asked Ramsey to fix it. Instead, Ramsey built a new one from scratch with the same clock-spring action as was used on the landing gear of the fighter planes of the day to retract the gear. This coiled spring fitted into a circular receiving cup. Two were used on the pedal, making it twin-springed.”

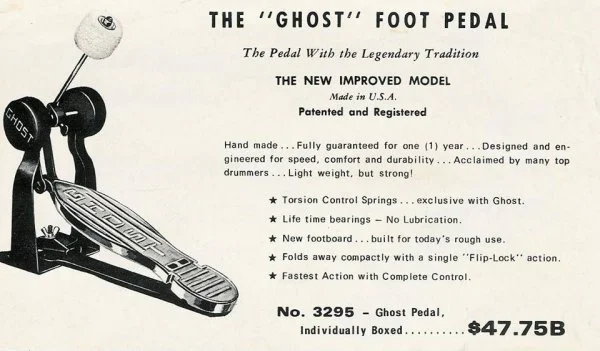

After his honorable discharge, Bob returned home and soon patented his pedal design. He sat down with Margie and asked her what to call the gizmo. She replied that since he discovered the action while aboard the Gallopin’ Ghost, in tribute he should call it the Ghost. He thought back to his time aboard the Enterprise, of the action he saw and the friends lost, and then of that fateful day at the machinist’s bench and he agreed with Margie. He hoped, as he would write in the pedal’s brochure, that the Ghost pedal would go on “to claim the respect of drummers and other musicians similar to the respect we all give the great ship from which it got its name.”

They built a machine shop in their garage to manufacture the new Ghost pedal and custom made all their own jigs and dies. Together, the couple would cast the larger parts out of aluminum and make the hardened steel springs that, diametrically opposed in tandem, would give the Ghost pedal its signature adjustable “Phantom Action.” Bob exclaimed to the Springfield News, “We put everything into hock- the house, the cars, and went $100,000 in debt to start the business.” Margie was touted in the Register-Guard as Ghost Products Inc.’s first drill press operator. Almost overnight, the best drummers of the day would be using Ghost pedals to elevate their playing to new heights.

Once someone played a Ghost pedal they had to have one. From drummer to drummer, stories of the Ghost spread first by word-of-mouth, until the Register-Guard printed testimonials of some of the era’s most prominent jazz drummers in a 1957 article about the Ramseys and their pedal. Shelly Manne, one of the first big-time drummers to embrace the Ghost pedal, said it was “without a doubt the most perfect pedal ever devised.” Cozy Cole, who played with Cab Calloway and Louis Armstrong, called it the “Cadillac” of drum pedals. Louis Bellson, who pioneered the use of double bass drums said, “My praise is twice that of the other drummers because I use two of them.” Lionel Hampton was a convert, and even Gene Krupa used one despite his endorsement deal with Slingerland drums.

Soon Bob and Margie updated the design, giving the pedal an art deco styling with the pedal’s mysterious moniker emblazoned prominently across the spring covers, finished in metallic battleship gray. The tip of the stylized footboard culminated in a point reminiscent of the bow of the Enterprise, with “GHOST” in all caps down the center bracketed by parallel lines which subtly evoked an aircraft carrier runway. For over 25 years Bob and Margie churned out Ghost pedals from their home, and by the late 1960s they were making almost 100 a week. After moving to a larger location and hiring a small staff including plant manager Roy Peeler, they soon increased their production five-fold to supply the nation’s largest musical instrument distributors.

“This thing just wouldn’t die,” Bob said of the Ghost pedal in the Springfield News. “It had every opportunity to fail but drummers just kept telling their friends…”

The competition was no match for the Ghost. Ludwig’s Speed King pedal was one of the preferred pedals of the day. Its design, however, required regular lubrication eventually earning it the nickname “Squeak King.” Throughout the 1970s more players flocked to the Ghost pedal until it reached cult status as a secret weapon among rock drummers, especially double bass drummers including rock greats Carmine Appice and Alex Van Halen. In a 2021 auction, Alex Van Halen’s 1980 Invasion Tour drum kit sold for $230,400, complete with two Ghost pedals on his double bass drums- just like Louis Bellson.

Despite her record of impeccable service, the USS Enterprise was eventually sold for scrap metal in 1958. Bob Ramsey gave up the Ghost in 1975, selling his business to Ludwig drums. He decided to retire after Margie underwent cancer surgery and felt that Ludwig was the right choice to continue the legacy, production, and distribution of the Ghost pedal. After all, William F. Ludwig Jr. described it as “a magnificent pedal,” and his new advertising campaign proclaimed the Ghost as “one of the world’s most uniquely engineered” and “most sought after pedals.”

Regardless of such acclaimed performance, like the Enterprise, the Ghost pedal would ultimately be scrapped as well. Ludwig would manufacture the Ghost for just a few more years until it was quietly discontinued in 1981, citing difficulty working with the coiled springs. By contrast, Ludwig’s Speed King pedal is still in production today.

In the end, Bob and Margie’s Ghost pedal serves as a fitting tribute to the Gallopin’ Ghost of the Oahu Coast. Much the same way that the Enterprise would prevail in battle despite the odds stacked against her, their Ghost pedal went toe-to-toe with the best pedals that Ludwig, Slingerland, Rogers, and Gretsch had to offer. This pedal, born from a flash of wartime inspiration and humble origins in the Ramsey’s garage in Springfield, Oregon had bested the industry titans of Chicago and New York. Even now, the air of mystery surrounding this fabled phantom pedal and its legendary story still circulates in the online drum forums and fan pages, its intrigue ever-beckoning a new crop of drummers to find out about the Ghost. Though Ludwig shelved it, Bob Ramsey was right- the Ghost pedal didn’t die, but continues to live on in the imaginations and under the feet of drummers to this day.

Original 1967 Ghost pedal press photo with Bob showing off the pedal’s wide range of adjustable action (photo Paul Petersen)

AMM2c John Robert Ramsey after receiving his Presidential Citation for the “Enterprise”

The Dauntless SBD-2s of Scouting Squadron Six in flight over the “Enterprise” and accompanying destroyer

U.S.S. “Enterprise,” the “Gallopin’ Ghost of the Oahu Coast” with her complement of aircraft that Bob maintained

1939 concert advertisement for Eugene’s King of Swing Bob Ramsey and His Band